Year: 2001

Director: Pierre Falardeau

Writer: Pierre Falardeau

Time: 120 min.

Genre: Drama

Here in Quebec, Pierre Falardeau is a real character, a caricature even. You see him regularly here and there, the eternal cigarette in mouth, the “common man” wardrobe, the Gainsbourg-style messy beard and hair, Falardeau being his belligerent self, bitching about everything, citing obscure writings, talking contemptuously about oppressors and their weak, almost willing victims… And through it all, an intense love for his almost country and an intense desire to see it finally free himself from Canada and be independent. But beyond the public figure, Falardeau is also an artist, even though it isn’t always obvious. You can see it in his documentaries, from the explosive visual poem “Speak White” to his anti-bourgeois diatribe “Le Temps des Bouffons”, in the cinéma vérité boxing movie “Le Steak”, and even in the original “Elvis Graton” short, a smart and hilarious cult classic. But then there’s the sequels, mostly lousy slapstick, and a couple of feature films made with good intentions but sloppy craftsmanship like “Le Party” and to a certain degree, “Octobre”.

“15 Février 1839” is a whole different story. This is the film Falardeau was born to make. He has wanted to tell the story of the Patriotes for nearly 30 years, ever since he read De Lorimier’s will, and he fought for years to get the money to produce it. You see, in Canada, like pretty much everywhere in the world, Hollywood movies take nearly all the place. It’s very rare for a local film to turn in a profit. Hence, the only way for movies to get made is through governmental subventions. The problem is that it’s then up to a small committee at Téléfilm Canada to pretty much decide what gets made and what doesn’t. And if you’re a loudmouthed troublemaker like Falardeau pushing a corrosive, anti-Canada film… Well, you get rejected, again and again, yet Falardeau didn’t give up. A group of artists and students raised more than half a million dollars, Falardeau made yet another shamelessly crowd-pleasing Elvis Gratton farce, “Miracle à Memphis” (which became the third highest-grossing film in Quebec history and put him in good standing with producers) and at long last, he even squeezed a little money from Téléfilm Canada and the film is now on screens across the province.

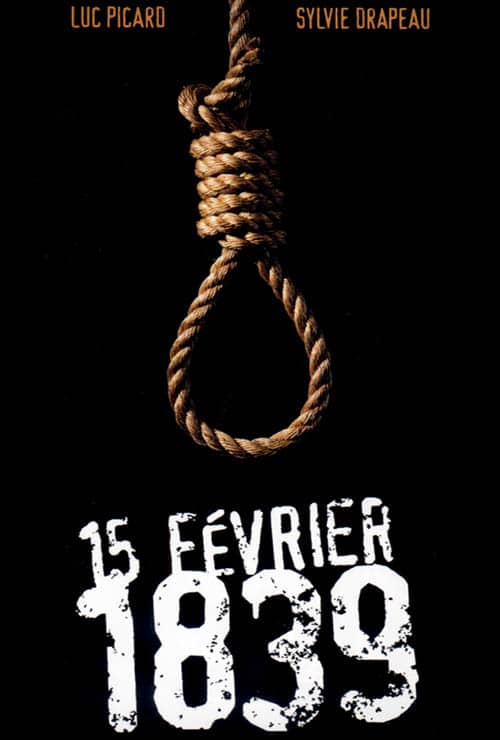

Was it worth all the hassle? Absolutely. It’s gotten nearly unanimous praise from local critics, and a nice reception at the box-office. I for one loved it. Falardeau has matured incredibly as a filmmaker, and his film affected me to my very core, both by reasserting my political convictions and by moving to tears with its universal human story. For even if you’re not French Canadian, this is a story that will resonate for anyone. This could be about Jews in concentration camps, Polish prisoners of the Russian or Africans who were jailed by the white dictators. Here, it’s about French rebels about to be hung by the British in 19th century Montreal, but that’s not the point. This is really the story of men who know they’re gonna die when morning comes, just because they fought for what they believed in. Race and origin are only details.

Luc Picard stars as François Marie-Thomas Chevalier De Lorimier, a French Canadian politician under Papineau who rallied up men across the Nouvelle France and led an insurrection against the British who ruled over the land ever since their victory over the French army in 1760. In the 1830s, some French were able to hold office, but they didn’t have any real power. They were still servants to the English. When the film begins, the revolution of the Patriotes is coming to an end. Inexperienced farmers fighting against the almighty British army, they were rather easily defeated, and the English rubbed it in, burning churches and houses, raping French women, stealing property and putting hundreds of men in prison without fair trial, many of them sentenced to death. The film spans over the last 24 hours in the life of De Lorimier. We watch him hang on to his principles, refusing to express any regret. He couldn’t stand his people being colonized and assimilated by the English and did something about it, and it’s not because he’s about to die that he will surrender.

So, as you must have guessed, the film is a “huis clos”. Following the impressive, mood setting travelling over burning farms and redcoats beating up people that opens the film, the movie never leaves the prison; no flashbacks, no “meanwhile…”. That’s somehow a financial decision (even if he had wanted to, Falardeau couldn’t have made an epic of “Braveheart” proportions), but it works artistically. With time running out all too quickly on De Lorimier, the movie grows more and more intense. There is a backdrop of dread and fear to every scene, but the Patriotes try to overcome it. De Lorimier, one of the few literate ones, finds refuge in writing, hoping that his words will carry on. Others, like Protestant Swiss Hindelang (Frédéric Gilles), who will go to the gallows besides De Lorimier, prefer to put on a defiant front and laugh before adversity, singing, dancing, telling dirty jokes…

There is also much political talk (these are political prisoners after all), and a lot of it feels all too actual. Liberty and independence are recurring themes, but not only Quebec’s: Patriotes talk about the similar fate of the Irish, or the Scottish. They discuss fatally how future generations might not learn from this and forget what their fathers fought for and lost. One of the film’s strongest sequences comes when De Lorimier’s wife Henriette (Sylvie Drapeau) comes to visit and see her man one last time. The two of them have the most tender of times together, and when guards tell Henriette their time is up, she has to forcefully torn from De Lorimier’s arms. Almost as wrenching is the exchange between two best friends held on opposite sides of the prison who have to yell each other how they feel, and the sad discovery from one of them (who will die the next morning) that a girl he had a crush on but was too shy to ask out actually liked him.

There is also a poetic thread in the film, as some of the men reminisce of the little things that mattered more in life. Sleeping in a nice bed against your soft, warm wife. Stream water hitting rocks. Trees come spring. Watching your son draw his first letters. The spiritual side of things is also touched when, in the last hours, a Catholic priest (Julien Poulin) comes to pray with the men. And then there’s the harrowing sequence in which De Lorimier, Hindelang and three other of their compatriots are let to the gallows. From the get-go you know these guys are gonna die, but it’s still as sad when the moment actually comes. It’s almost impossible to imagine the despair that must go through you when you feel the hanging rope being placed around your neck and must wait for the trap to open, sending you in the great unknown…

“15 Février 1839” is an amazing film which finally positions Falardeau as a bona fide artist. His script, written with the help of the late poet Gaston Miron and Paul Buissonneau, is rich and multi-layered. Sure, the politics sometimes border on propaganda, but as Falardeau said in interview, “this IS a black and white situation: there’s the hangers and the hangees. When Spielberg made “Schindler’s List”, did anyone ask if he was treating the Germans fairly?” So this is an angry movie, a partisan movie. In the era of political correctness, this is a breath of fresh air. Falardeau also surprises with his direction, sober but effective. Working with wonderful cinematography by Alain Dostie and a beautiful score, he crafts a movie of quiet beauty and great emotion, especially in the scenes between Picard and Drapeau, who both give powerful performances. “15 Février 1839” inspires politically, but it does so by focusing on the human side of its story, which makes it all the more memorable. This is one of the best Canadian films I’ve ever seen.